Awakenings tells the tale of Dr Malcolm Sayer and his efforts to treat catatonic patients who survived an epidemic of encephalitis lethargica. This film, with its compelling and poignant story, can be explored from a number of perspectives.

With an expert cast comprising of the likes of Robin Williams, Robert De Niro, and Julie Kavner, the portrayal of the characters was naturally one of the main elements that contributed to the audience’s experience of the film. Williams, at his most restrained, brings to life the role of socially inept neurologist Malcolm Sayer wonderfully, but it is De Niro’s performance as newly “awakened” Leonard Lowe which really captivates. Depicting the progression from awakening to dyskinesia to the eventual return to a catatonic state, De Niro is unafraid to portray the more unsightly Parkinsonian symptoms, made all the more evocative with the way he captures Leonard’s struggle for autonomy and freedom. Dr Sayer and Leonard’s burgeoning relationship after the latter awakens is undoubtedly heart-warming to watch; however, their increasingly strained relationship culminating in Leonard’s attempt to leave the hospital was played by their actors so well that as the audience, we empathize with both Leonard’s need to be free of the confines of the hospital and Dr Sayer’s growing realization that the drug is losing its effectiveness on his patients.

De Niro's uncanny efforts to immerse himself in the Leonard's remarkable pathology and his relationship with Dr Sayer

When Leonard’s attempt to leave was thwarted, we see his resistance become increasingly physical. This behaviour can, in part, be explained by the frustration-aggression hypothesis, which posits that unresolved frustration triggers a readiness to aggress (Berkowitz, 1989). In the context of the film, Leonard’s frustration stems from his inability to go for a walk as and when he pleases, to be free. The hospital staff is seen as coming in between him and his goal. This causes him to lash out at them in retaliation, in line with the hypothesis. Alternatively, Leonard’s hostile behaviour is consistent with the side-effects associated with the drug L-dopa (Hoglund et al., 2005), which could provide another explanation for his aggression and paranoia towards Dr Sayer and the rest of the staff. Despite this, the need for freedom does not appear to be a theme isolated to just this particular arc in the film; early in the movie, Lucy, not yet awakened, walks to the window instead of the water fountain as Dr Sayer and the nurse Eleanor had thought. This lends insight into the inner workings of the patients, highlighting not a will to survive, but a will to live.

Dr Sayer attempts to understand Lucy's motivations

As the rest of the patients awaken during the movie, it becomes easier for both the audience and the hospital staff to see them as people with their own personalities and feelings. By the end of the movie, the patients have reverted to their catatonic states, but not all is it once was. Gone was the original ambience of the “Garden ward”; the patients were now receiving more than just basic care, with the staff treating them as individuals capable of dignity and worthy of respect. As a psychology major, this prompts a discussion on how we view patients in persistent vegetative states in real life: Are we not much like the nurses and caretakers of the Garden ward, as they are at the beginning of the film? Should we not strive to treat such patients more like their families do, like Leonard’s mother did? And to a greater extent, how to we define personhood? As the film highlights, just because we do not perceive a person as being conscious does not mean that they are unaware of their surroundings. One’s inability to care for themselves or communicate does not warrant half-hearted treatment and support.

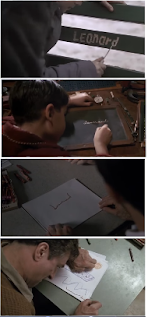

Aside from the physical portrayal of Leonard's symptoms, it was interesting to see how the progression of his illness was depicted through close-ups of his writing his name, something that seemed to be recurring throughout the movie. In addition to this, Dr Sayer notices a spike in Leonard's EEG readings in response to his name being called out. Indeed, a person's name is very much tied to their sense of identity, leaving one to wonder, what must it feel like when all you have left is your name?

Final Thoughts

At its core, Awakenings celebrates the joy of life and the healing exchange that can occur between doctor and patient when caring, rather than curing, is the emphasis of treatment. The title of the film also carries a double meaning as the hospital staff undergo an awakening of sorts themselves, with the staff exhibiting more care towards the patients after having interacted with them as normal individuals. Although the effects of L-dopa eventually sent Leonard careening helplessly back to his original state of immobility, his presence does manage to inspire Dr. Sayer to break free of his shell deepen his relationship with Eleanor. Furthermore, the content of the film was thought-provoking and does leave the audience with several questions:

Although there were problems with L-dopa, it does provide grounds for the discussion on what other seemingly impossible diseases may be cured. Ultimately, the film reminds us of the preciousness of the little things we take for granted in life, such as feeling, fantasy, risk, love, and wholeness.

References

The progression of Leonard's disease as depicted by his name

Final Thoughts

At its core, Awakenings celebrates the joy of life and the healing exchange that can occur between doctor and patient when caring, rather than curing, is the emphasis of treatment. The title of the film also carries a double meaning as the hospital staff undergo an awakening of sorts themselves, with the staff exhibiting more care towards the patients after having interacted with them as normal individuals. Although the effects of L-dopa eventually sent Leonard careening helplessly back to his original state of immobility, his presence does manage to inspire Dr. Sayer to break free of his shell deepen his relationship with Eleanor. Furthermore, the content of the film was thought-provoking and does leave the audience with several questions:

- How do we define recovery? Is it measured by fully regaining prior function, or do we instead consider small but incremental progress?

- What is the ethicality of administering trial drugs on comatose or catatonic patients? Granted, Dr Sayer did obtain consent from the patients' guardians, but how would their relationship to the afflicted affect their decision?

- The administering of L-dopa did result in the patients waking up, but what could then be done for individuals who wake up to a disrupted and derailed life? Should it still be administered, with the knowledge that the effects are only temporary?

Sayer highlights one of the dilemmas present in the film

Although there were problems with L-dopa, it does provide grounds for the discussion on what other seemingly impossible diseases may be cured. Ultimately, the film reminds us of the preciousness of the little things we take for granted in life, such as feeling, fantasy, risk, love, and wholeness.

References

Berkowitz, L. (1989). Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 59.

Höglund, E., Korzan, W. J., Watt, M. J., Forster, G. L., Summers, T. R., Johannessen, H. F., ... & Summers, C. H. (2005). Effects of L-DOPA on aggressive behavior and central monoaminergic activity in the lizard Anolis carolinensis, using a new method for drug delivery. Behavioural brain research, 156(1), 53-64.